*This is the original version of “High Court detention-centre decision highlights duelling forces in migration,” The Interpreter, 11 February 2016.

On 3 February 2016, the Australian High Court ruled its offshore detention centres as lawful institutions. It is a country’s sovereign right to determine how to treat asylum seekers in their territory. The High Court’s decision is significant as it is an indicator for the government’s dealing with asylum seekers and refugees in future, including the 12,000 Syrian refugees Australia has promised to receive.

Migration is a complex human phenomenon, which has generational impact on both sending, transiting and receiving countries. For making decisions on migration, a state needs to consider various factors from national security, demographic challenges, aging population, transport and social services, economic growth, ethnic diversity as well as public opinion.

Before elaborating this complexity, let’s get the basic terminology right. There is a great deal of confusion, and a serious misconception, on the references to migration in general. This lack of proper understanding can create bigger problems with manipulating public opinion and making myopic decisions in an area of policy vital for Australia’s long-term economic and social future.

First, not all migrants are immigrants. Migrants are those who are on the move in general. They are, therefore, temporary in nature. They keep moving. On the other hand, emigrants are the ones who leave their country of origin. There are different routes to become immigrants: labour and economic, family and humanitarian. Refugees belong to the final group of immigrants.

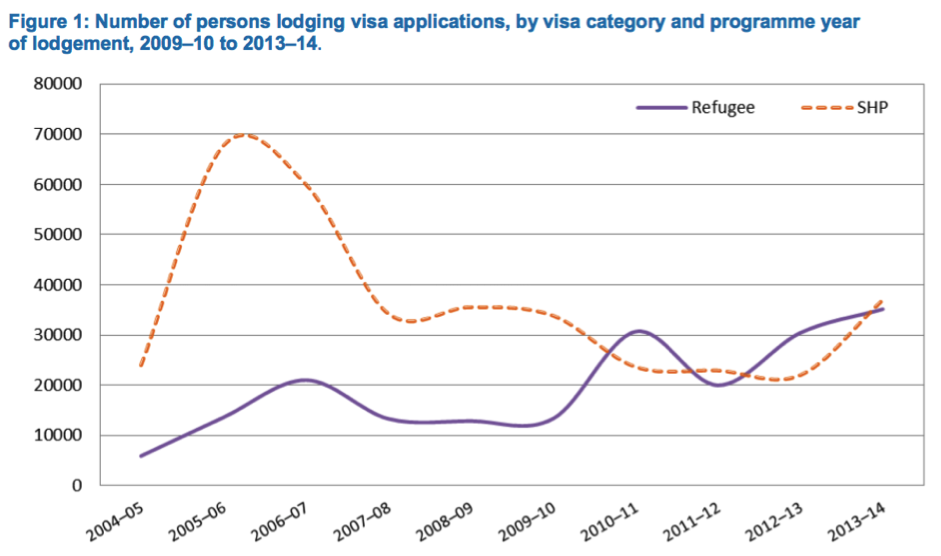

*SHP: Special Humanitarian Programme

[Source: Australia’s Offshore Humanitarian Programme 2013-4, DIBP, p.4]

Second, not all asylum seekers are granted refugee status. The former are those who’re seeking temporary shelter and protection from a well-found fear of persecution. If their applications are successful, they become refugees with temporary residency status. In 2013-4, 72,162 persons applied for Australia’s humanitarian visas (see above the table for the numbers of annual lodgings). Around 13,750 individuals and their families were granted this status. State parties to the 1951 Refugee Convention must comply with the principle of non-refoulement (no return to the country where they face persecution) and provide humanitarian assistance to asylum seekers. Australia has been a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its Protocol since 1954 and 1973, respectively.

Third, asylum seekers and refugees are not criminals who are detained in state sanctioned institutions. They are the ones who need help for “humanitarian”, not legal, grounds. People smuggling is a criminal act, defined in the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime and its Protocol on people smuggling that Australia is also a party to.

When refugee smuggling takes place, which is the case with most boat arrivals in Australia, two principles of international law compete against each other: protecting refugees, on international humanitarian grounds, on the one hand, and defending national borders as the sovereign right of the state, on the other. The High Court’s decision is to raise the hand of the border protection regime at this round of battle.

At the next round, Australia needs to prove that it is a responsible member of international society that respects international law, humanitarian principles and human rights. It is, however, a difficult battle to fight. Human rights do not always win but are traded off with other national interests. Increasingly so, these days. Even in Article 13 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the right to mobility is only halfway through the migration process. It only defines rights to leave and return to one’s country of origin. There is no human right to reside in a country not your own. That is a sovereign right of the hosting country. Humanitarian and human rights principles alone are losing ground against national security, sovereignty and territorial integrity.

A rational, not moral, approach for asylum seekers to safely reside the Australian territory, not in offshore detention centres, necessarily requires an understanding of the complexity of migration and its uncertainty and unpredictability, as well as its neglected potential to contribute to Australia’s economy and society.

Migration has multiple causes and consequences. It can be both positive and negative for the hosting society. The media mainly portrays negative aspects of migration: that migrants pose potential threats to national security, economy and cultural identity. The Boston, Bangkok and Jakarta bombings were prime examples to exaggerate this threat perception. Stories about migrants’ bringing in radical ideas and networks, taking local jobs, raising housing prices, increasing crime rates and spreading diseases are standard fare in today’s newspapers.

What is neglected, however, is that most migrants, especially refugees, are healthy and educated individuals in working ages. In evolutionary biological terms, they’re the fittest survivors, who outlived wars, violence and poverty. They have immense potential for the country’s economy. The 2014 OECD reports that migrants accounted for 47% of the increase in the workforce in the US and 70% in Europe over the past ten years. They fill important niches both in fast-growing and declining sectors of the economy. They contribute more in taxes and social contributions than they receive in benefits. Migrants boost the working-age population and contribute to human capital development of receiving countries.

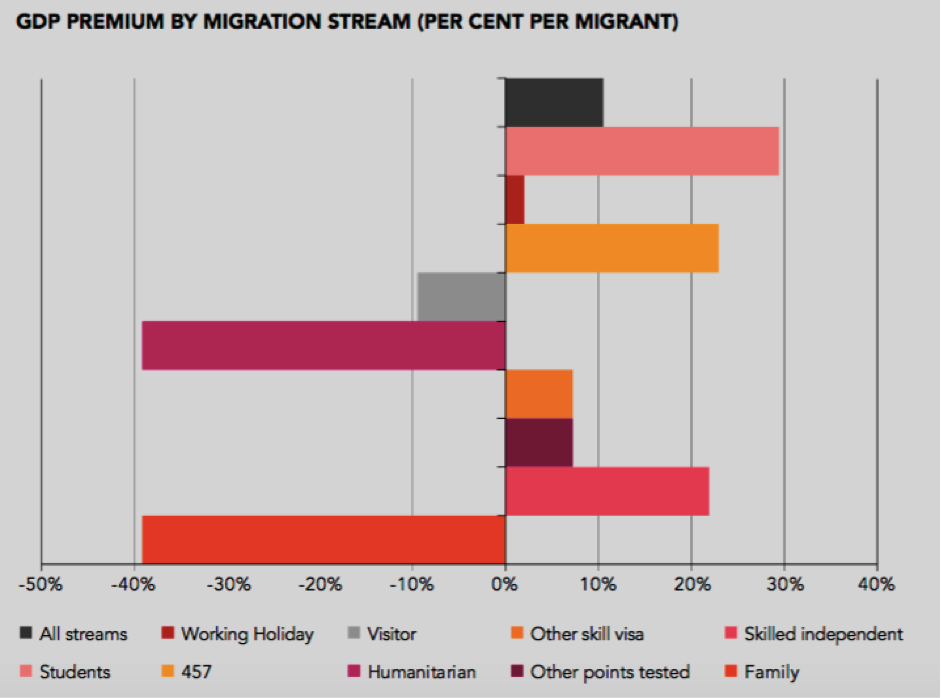

In Australia, the projected population by 2050 is 38 million. The Migration Council Australia finds that migration will have added 15.7% to the workforce participation rate, 21.9% to after tax real wages for low-skilled workers, and 5.9% in GDP per capita growth.

[Source: Migration Council Australia, The Economic Impact of Migration, p. 17]

Modern Australia is built by migrants. We’re all migrants or children of migrants. Without migration and with the current fertility rate, Australia can’t sustain its place in global economy. Survival is not just about the growth of GDP: it is also about resilience, societal fitness and diversity in order to maintain comparative advantage in a rapidly changing world. Refugees can offer human capital.